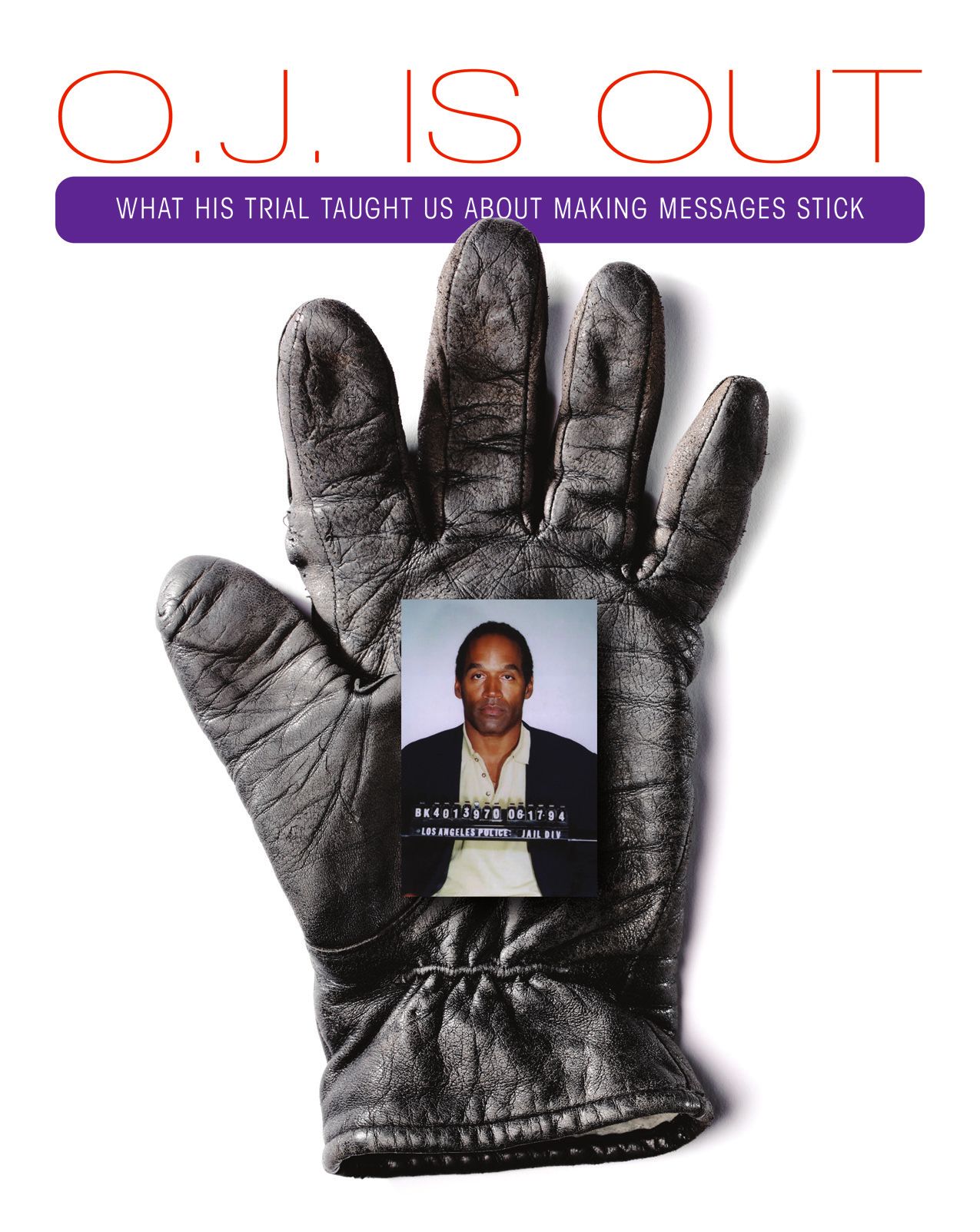

O.J. Simpson’s parole, which took place in early October 2017, resurrected a story that carried important social and legal ramifications from its beginning. But perhaps what’s equally interesting about this story is that it never really went away.

Recently, I was addressing a room full of engineers on the topic of effective communication, and with no prior warning, I simply asked the group to complete the following sentence, “If the glove….” Barely was the third word out of my mouth when the entire room, proudly and in unison, chimed out “….doesn’t fit, you must acquit.”

Think of how remarkable that is. Most of you reading this article can barely remember 15 percent of the last PowerPoint presentation you attended, yet most adults over age 35 can unfailingly and instantly summon that phrase from 20 years ago.

Of all the legacies the O.J. case left us, the power and stickiness of an idea is one of the most interesting. The case’s memorability teaches a lesson in communication that most of us would do well to learn.

We all aspire to be more effective communicators. We want our ideas to stick and persuade. Yet, we somehow know that all those tips we’ve heard (have positive and confident body language, build rapport with a personal story, have fewer bullets on your slides) might possibly be helpful at the margin, but they cannot be the real answer to creating the impact and stickiness we want.

And we’re right. No one remembers the immortal “If the glove …” phrase because Cochran accompanied it with wonderful eye contact. As it turns out, that stuff doesn’t actually matter at all.

As plentiful as they are, all those checklists (See related article on page 42) designed to help speakers engage better, make their messages stick and drive their audiences to action—however well-intended—are overwhelmingly missing the single, central bit of wisdom that in fact makes a difference:

It’s all about ideas.

If we truly want to understand communication, we must ground ourselves in an understanding of the human brain. When communication misaligns with the way our brain consumes information, failure is all but guaranteed. Conversely, when we align with the way the brain consumes information, and particularly with the way the brain makes decisions, spectacular success is placed firmly within our reach.

Of all the things we need to understand about the brain, the most important is this: The brain doesn’t really love facts and data. It finds them difficult to store and retrieve, especially in large quantities. But what the brain really likes and “traffics” in are ideas.

Think of the brain as reductionist—it automatically reduces information to the level of ideas. Ideas contain the distilled essence of a broader set of information, and they are far easier to store and retrieve.

Cochran understood this. His famous seven words and their impact show the power and stickiness of an idea. His jury was swimming in seven mind-numbing months of prosecution testimony. In a sea of facts and data, they were desperate for one simple unifying idea that would make sense of it all. And that’s exactly what he gave them.

This famous example really helps us to see the most critical of all principles of communication. If you want to make a message really stick, doesn’t it make logical sense that your best hope is to present your audience with exactly the kind of information that their brain is most comfortable handling and storing?

Thus, at the highest level, the ultimate goal of any communication is not to make an audience laugh, to make an emotional connection or to maintain eye contact. Rather, it is this:

Powerfully land a small number of big ideas.

And yes, that is my big idea. This is the single most important governing rule of communication. All great communication is great precisely because it adheres to that principle. Think about Martin Luther King Jr., The Gettysburg Address or the last few mind-numbing PowerPoint decks you were exposed to (or, sadly, delivered). To accomplish this, the first critical task is to identify what your big ideas are. This begins with asking yourself what action you want your audience to take. Fund a project? Buy a product? Approve a budget? The purpose of virtually every presentation is to drive an audience to take action.

From there, you can work back to determine your big ideas. The reason why this works is that, in human beings, action is preceded by belief. One of our clients sells a technical solution to the chemicals industry. In designing their sales message, my client understood that no matter how good their solution was or how high its value is, the customer won’t be interested if installing it is disruptive to their smooth running or causes plant downtime. Hence they determined that one big idea that must be central to this sales story is, “The migration to our solution is remarkably painless.”

That single big idea is worth—and has replaced—a hundred PowerPoint slides. Since rolling out the new messaging, the firm’s sales results have taken a marked turn for the better.

Once you’ve found your big ideas, you can find the best way to support them using data and story.

The final step is to organize them into a logical narrative. Don’t just present your ideas as random objects. There will be a natural way that the story will want to be told. Take the time to find it. The result? Instead of a meandering presentation bloated and overflowing with facts and data, you’ve created a tight, crisp and sticky argument based on a few big ideas. It’s your very own, modern-day application of, “If the glove doesnt fit..."